My mother outlived my father by several years, and when she died, my sister and I faced the sysyphean task of cleaning out their house. This included going through my father’s shop in the basement and in the garage, where he did everything from making wooden lamp bases on his lathes, to machining new parts for his car, to carrying out scientific experiments. I’m fairly certain that he never threw anything away. Nothing.

For my sister and me, each decision to keep or discard bore an emotional weight that devastated us both. It took some months, and we were weary in heart and soul both during the task, and for a long while after. Frankly, it would have been much easier for us if my parents had followed the modern art of “tidying-up”. But if they had, so much would have been lost.

The word souvenir comes from the French: a thing that makes you remember. And, perhaps that is what exhausted us so much: every little item we found had a memory attached. My mother’s battered ancient fruitcake tin, where she kept her needles, pins, and thread, and which was always hidden under her chair in the living room. My father’s homemade work aprons that had so often been our gifts to him on father’s day or his birthday.; his navy insignia; his little leather notebooks where he kept lists of books he wanted to read, recordings he wanted to buy, the names, ranks, stations, and bunk numbers of everyone on his ship during World War II, poems he wanted to remember, a recipe for applejack eggnog. Even my grandmother’s things were still enmeshed in the collection: her vanity set; her hair ornaments; her love letters. My sister dissolved into tears one evening when we had finished. “I feel as if I am throwing Mom and Daddy away.”

But the reality is that we couldn’t keep it all. So painstakingly, emotionally, and exasperatedly, we combed through the house as if it were an archeological dig. And, in a way, I suppose, it was.

Among the things I found was a dirty metal file box with little plastic drawers for sorting diodes, resistors, and transistors and other early electronic parts. The box had stood on my father’s workbench for as long as I can remember. At the top was my name, printed out in the same style as the labels on each drawer.

I remember the day my name came to be on that box. I was about three, and my father had received a new gadget in the mail: a label maker that used long flat spools of plastic to impress letters on. It was an exciting thing. I remember my father showing me what it did by painstakingly printing out the letters of my name, and then pasting the result at the top of the box.

Seeing that box on his workbench, years after his death, brought me fully back to that moment. I remembered the smell of cut metal and wood, the difficulty of seeing the top of the bench unless I were given a little stool to stand on. I remember my pride in seeing my name on the top of that box, and mostly, I remember being loved as clearly as if I had been embraced.

There is a–by now–somewhat aging trend in the world of home interiors known as “tidying up”. The process, which is a method of decluttering and living a minimalist life, has an almost spiritual quality, in that it claims it will change your life, and its adherents have the tone and enthusiasms of Nineteenth Century evangelists.

There is a vaguely moralistic and superior tone taken by these doyens of home organization. They are the new Puritans. No one needs stuff. No one needs other people’s stuff. It is clutter. It clutters your home and your life. In this age of materialism, when we all have bulging closets, attics, basements, and enough stuff to create another entirely separate household, people’s interest in the process is perfectly understandable.

There is a vaguely moralistic and superior tone taken by these doyens of home organization. They are the new Puritans. No one needs stuff. No one needs other people’s stuff. It is clutter. It clutters your home and your life. In this age of materialism, when we all have bulging closets, attics, basements, and enough stuff to create another entirely separate household, people’s interest in the process is perfectly understandable.

But, had my father not kept his old things–radio parts that were no longer needed by any working radio–my memory of the label-making would have been lost to me, for there would have been no material thing in the world to remind me of it. That moment would have been lost to me forever.

This is the value of things, perhaps, even, of clutter. It is memories that make us who we are; which haunt us; which enrich and warm us; which remind us of how to be better. And the things, they are the memory triggers. They bring back the moments we might have forgotten in the depths of time: of my mother in her kitchen, or cutting off a button thread with her teeth; my grandmother combing her hair, of picking her up at the bus station and sitting next to her in the car, touching the softness of her fur coat; my father listening to opera at high volume while he worked on his car. These are moments that form us; that make us ourselves.

I will admit that I have kept too many things. We jokingly refer to our garage as “the home for wayward chairs.” I have much of my parents’ good mahogany furniture, their wing chairs and their china cupboard. I have my grandmother’s vanity. I have all my father’s designs, and the paperwork for his one hundred twenty-something patents. It is a lot, and it can be overwhelming sometimes.

But I’ll take clutter any day. It is the price of remembering how it felt to be a little girl who was loved by her father.

Tidying up, indeed.

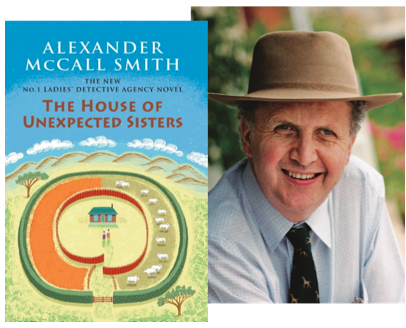

It is difficult–if not impossible–to say anything original about a man so well-known, and, indeed, a Commander of the British Empire, but my attempt follows:

It is difficult–if not impossible–to say anything original about a man so well-known, and, indeed, a Commander of the British Empire, but my attempt follows: I’ll be chatting with novelist and host Cynthia Hammer on her show, Hammer Away. Wednesday November 1st in the 4 o’clock hour, Central Time. You can tune in to latalkradio.com from your mobile device, or go to

I’ll be chatting with novelist and host Cynthia Hammer on her show, Hammer Away. Wednesday November 1st in the 4 o’clock hour, Central Time. You can tune in to latalkradio.com from your mobile device, or go to

So, you ask: Now what will you do? Revel in the freedom? Drink champagne, or possibly bourbon? Walk the dogs? Go to Disney World?

So, you ask: Now what will you do? Revel in the freedom? Drink champagne, or possibly bourbon? Walk the dogs? Go to Disney World?