Gratuitous Dog Photo

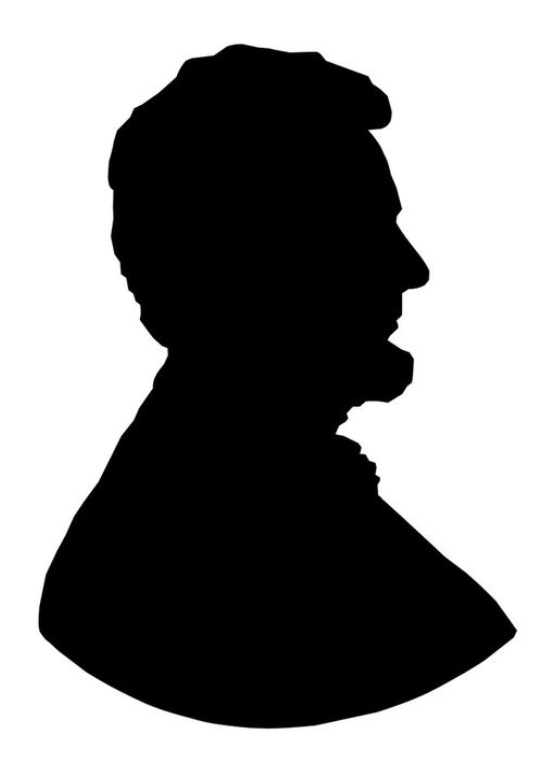

Today is Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. It bothers me that we have lumped Lincoln’s and Washington’s birthday’s into one generic Presidents’ Day. They were not generic men; each in their particular ways were fathers of new eras in the American experiment. It bothers me still further, that at a recent trip to an elementary school, even the third graders didn’t know who Lincoln was, or recognize that distinctive profile. It’s a subject simple enough for kindergarteners, but we seem to assume that children are incapable of learning things these days.

As a former teacher—and lifelong admirer of President Lincoln—I consider the abandonment of history a disgrace to our schools. Not to mention the abandonment of grammar, literature, and civics and…just reading. If you don’t believe me, look at the statistics. I’ll wait.

Children are sponges. They love knowing things, and their brains are programmed to memorize facts. It’s what human beings are meant to do. The education establishment dismisses memorization as mere rote learning—as if memorizing is somehow wrong. But I see memorization both as a gift and as the proper preparation for thinking. And at any rate, it would be a nice start.

I saw this close-up and personally when I was helping my grandson with his algebra this fall. How do you factor if you haven’t (in second grade) memorized the multiplication tables? It’s a form of rote learning that forms the facility for all the mathematics that follows.

Literature, too, is aided by youthful memorization. Children may not be ready to grasp the depths of meaning or the literary allusions in a memorized poem. But they internalize everything. Once memorized, the poem belongs to them in their own personal library to be recalled at will, or to arise unbidden at an apposite moment. And because it is theirs, their understanding gradually develops as they mature. They internalize the rhythms, too, and those old lines roll up like waves in the unconscious, building a sense for the language and its music. These things form good writers and appreciative readers, and create a common cultural underpinning that bonds us as human beings.

And history—that rhythm of ascent and failure that we repeat as civilizations and as individuals—begins with facts. Who did that? When was that? What happened first? What happened next? It’s only armed with these facts that we can form any opinions of what we think. You can’t think about history without knowing its essential details. And if we don’t know essential details, what do we have to remember?

The millennia-old tradition of education was that children go to grammar school to memorize—history, grammar, languages, literature, scientific and mathematical facts—until the age of twelve. At twelve, having reached the age of reason, they begin their true education. But that education is based upon the foundation of everything built before.

On this day in 1809, a great man of American history was born in a log cabin in Kentucky. He was a poor farmer’s son, and his life grew terribly hard when his beloved mother, Nancy Hanks, died at age 34 of poisoned milk. But his step-mother, the determined Sarah, encouraged him to read, and insisted that he educate himself. And read he did—whatever he could find—after a grueling day of manual labor, by the fire light. His speeches and letters reflect how deeply he internalized the great literature of his time, how influenced he was by the Psalms, by Shakespeare, by Milton, by the ancient Greeks. He walked miles to borrow—and return—books. He read widely and deeply, and he memorized. Today, if we have any sense, we look back and honor him for his righteousness, his valor, his humanity, and his martyrdom to the cause of freedom. He was an honorable man, worthy of being honored.

I didn’t use a book to look this up this morning. I learned it in elementary school.

It makes me sad that so many Americans did not.

He’s sound asleep and snoring with his nose buried in the small of my back. It’s very warm and tickly, but so sweet. And of course, I can’t move.

My friends, Evelyn and Rose, are twin sisters, age 93. I have known them all my life. They have their share of challenges, as do we all, but they are utterly undiminished by age in any meaningful sense, and carry on with rare gallantry.

Today, for my birthday, they sent me not one, but two bottles of Veuve Clicquot, all beautifully packaged in a big box with excelsior that feels like a beautiful and elegant difference from plastic bubble wrap.

I think it will be a a very happy night. Or possibly afternoon.

When I wrote to say thank you, Evelyn said, “We know what you like.”

It’s nice to have friends.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about a turkey I saw helping another turkey. Some readers were skeptical—which I might be, too, if I hadn’t seen it myself—about whether animals demonstrate altruism.

But increasingly, after centuries of human conceit about our moral superiority, science is being forced to acknowledge that animals do demonstrate care for their communities, sometimes even for other species. Today’s New York Times story about a male elephant seal rescuing a drowning pup is another example of an animal’s taking action that was not necessarily in its own interest.

This past fall I saw another incident of turkey community action. The turkeys were on their daily march back to our woods to roost. The big toms were in front, and there were several groups of hens, surrounded by eleven scrambling poults—I counted—following about forty feet behind. Herding cats has nothing on herding turkey poults.

Our ravine is a water conservancy, which means there are some fairly deep holes that are usually dry, but fill with leaves in autumn. They seem like solid ground, but you can sink pretty deeply (and turn your ankle) if you accidentally step in the wrong place.

As I watched—seeing the babies is rare— the poults, one by one, managed to just barely avoid the biggest hole, scattering around it. Holding my breath, I could see what was about to happen: one took the wrong line, and promptly disappeared deep into the leaves. Its frantic peeping was terrible to hear.

Instantly the line stopped, and the toms turned and raced back to the sound of the crying poult. Soon the whole flock was surrounding the area—not in an orderly way at all—but homing in on the baby. I turned my head at exactly the wrong moment—dogs, you know—but suddenly the peeping stopped, and when I looked back, the adults were reassembling into the line, and I counted: one, two, three…all eleven poults were there. Counting turkeys can be tricky, so I counted three times. Everyone moved back into line, and on to the assembly grounds to carry on with their evening routine.

I still don’t know how they got the poult out of the hole.

It’s completely normal for parents to risk all for their offspring, and in this case, the poult was likely genetically linked to the adults who sped to its rescue. But to see the entire flock work together like that was another lesson to me. We humans have to learn a thing or two, and meanwhile, maybe we should stop being so smug about ourselves.

I had a little meeting with a local book club yesterday. They are all old friends, and did more talking than I did, and mostly on topics unrelated, but I’m not in a position to criticize digressions.

I almost always enjoy meetings with my readers, because by definition we have something in common, and people who don’t like my books generally don’t come to hear me speak. There was one notable exception: a book club on Washington Island shortly after my first novel came out.

It was a luncheon meeting, just before Easter, and after a pleasant lunch we all sat down for the meeting. One woman spent the entire discussion rapidly paging through the book to find things she didn’t like. She found many. Another pointed out that the map in the front was inaccurate. Another remarked how unrealistic the book was, since in her thirty years of living on the Island, she had never been invited to sit in the ferry’s pilot house. I wish I had had the nerve to say I could see why. Nor did I point out that my book was a work of fiction, only loosely based on reality. Until then, I hadn’t imagined it would be necessary.

It was an excruciating hour, and I was longing for a stiff drink. As the ladies filed out, I sat, somewhat shell-shocked. One leaned over to whisper as she went out.

“I liked it.”

Afterward, in need of some fresh air, I headed down to the ferry office to pick up a package. As I was leaving, there were some guys down at the dock calling and waving at me. “He’s mad at you for not telling him you were here,” the crewman joked, pointing at the captain. I went over to chat with them, relieved to see some friendly faces. “We’re heading out. Want to come for the ride?”

So we did a little round trip on the ferry, while I sat in the pilot house with the crew, entertaining them with the story of the book club meeting. They were able to identify everyone who was there by my descriptions, laughed about the surliness of the book-paging woman, and told stories of her rudeness. The conversation progressed to some fascinating stories about life on the Island. By the time we returned, I was in a much better mood.

So, I did say I don’t mind digressions. But my actual point is: if you live within a reasonable drive of Milwaukee, and would like to host a book talk, you can contact me here.

But only if you like my books.

I’m keeping my nails ridiculously short these days. It’s partly because I am playing the piano again, and partly because getting my nails done bores me. I am at the point in life when I don’t want to waste my time. And I am not trying to impress anybody.

There is a fairly thin line between feeling free to do what you want and letting yourself go. It’s a much thinner line for women than for men. Gray-haired men look distinguished. Gray-haired women usually just look old. I have a friend who decided to stop coloring her hair, and she looks fabulous. Not everyone does.

Most days, when I am at home writing, I still do my hair, wear mascara, and make an effort to look nice. I partly do it so my husband isn’t horrified (not that he would ever say so, even if he was). But I mostly do it for myself. I feel crummy all day if I don’t make some effort, even if it’s not all that noticeable to anyone else.

I have two particular women I always keep in mind as examples. One is someone I knew quite well. She was a friend of my mother’s who lived to be 108. Her name was Blanche, and I got to know her as an adult when we were both docents at a tiny art museum. Even though we worked together, I never dared call her by her first name; it would have been disrespectful. She was an alert and intelligent nonagenarian, and every time I saw her—even at her own home—she was nicely dressed, wearing a touch of makeup and a little bit of jewelry, and looking nicely pulled together. She was never overdone. But she took care.

The other is someone I never even met. Some years ago I was invited to speak at the opening of a museum exhibit. I only knew the curator and some of the museum staff, so after I did my part, I had the pleasure of carrying a glass of champagne while I wandered alone in a gallery of Dutch masters. This, I confess, is just about my favorite thing to do in the world, and I rarely miss an opportunity to hang out at the National Gallery. It soothes me.

But, as usual, I digress.

On my rambles, I noticed an elderly lady being shown around the gallery by one of the museum staff. He was attentive. She was clearly interested. She looked carefully. She asked questions. She spent more than the polite amount of time with the paintings. She was slim, white-haired, and elegantly dressed in black. She projected both strength and grace, while also being impeccably stylish. I asked who she was. She was Roberta McCain, John McCain’s mother.

Later, as I waited for a cab, I watched as one of the valets brought up a tiny hatchback. He handed the keys to Mrs. McCain, and she drove off alone. I don’t know exactly how old she was then, but she, too, lived to be 108.

I think often of these two women: one a small-town girl in Wisconsin, the other the daughter of an oil tycoon, wife of an admiral, and mother of a war hero and senator. What was their secret? Genetics, no doubt, were a factor. But wealth clearly was not. Nor was a life without worry. What kept them going? Faith? Curiosity? Generosity? Friendship? Or just plain stubbornness?

I can’t help thinking that there is a connection between longevity, having interests in larger things, and a willingness to make an effort. And so, I continue to try. I think it is a signal to yourself that you are worthwhile, and that you are not idling somewhere in a back room. You are prepared to meet the world. You are in the world. That matters a lot, I think.

But I also wonder whether art museums are a wellspring of long life. It’s a theory I am happy to test. Any time.

Every year I ask for a blizzard for my birthday, which is this week. So far, I have only gotten two, and I think the odds are long for any kind of cold weather this year. The snow is almost gone, it’s warm and damp and muddy, and it’s my least favorite kind of weather.

Despite my best efforts, the dogs track in mud, and if I’m not meticulous, leave splatters on the walls and cabinets. If I forget to close the doors to the bedroom, they leave mud on the bed. There are old beach towels spread everywhere in varying stages of dirt and dampness, and it takes time and effort to diminish the squalor.

On top of everything else, it’s too warm for a fire in the fireplace, which doesn’t draw well above 45F.

Complaining about the weather is a human pass time, I suppose, but it annoys me, particularly when I do it myself.

The dogs, blissfully uninterested in the weather—unless it’s raining, in which case they are frustrated when I won’t make it stop—are sound asleep nearby. A pair of red-tailed hawks are on the hunt in the woods, and I do not see a single squirrel or small bird anywhere.

There are worse things in life than bad weather, so we will count our blessings, instead.

Time for more coffee.