I had a busy night planned. It involved cleaning out a cupboard where mice had been and sanitizing and rescuing the framed family pictures that had been stored there when I repainted the stairway a year ago last November. I was planning to hang the pictures—about a dozen or so—in the repainted hall. I wanted to tackle this disgusting job so I wouldn’t be ashamed in front of my cleaning lady. (It was, in actual fact, another clever procrastination technique in my novel-writing avoidance scheme. But I digress.)

Instead, as I was elbow deep in sanitizing wipes and thinking words that would have shocked my mother, my husband called my grandson from upstairs—and me—to come into the kitchen. My husband has a mischievous sense of humor, and is fond of calling me on the phone from upstairs, or summoning me from various tasks to show me something entertaining. I was not amused. “I am in the middle of something,” I said, forgoing the opportunity to explain the precise substance I was in the middle of.

“This,” he said, “is serious.” He then read aloud an email from our grandson’s math teacher.

Only yesterday we were celebrating an excellent report card. But something had gone awry in the past four days since grades were closed, and we were exhorted to ensure that tomorrow’s test did not reflect yesterday’s quiz.

My husband, whose confidence in me is sometimes misplaced, assured my grandson. “Grandma is great at math. She will be able to help you.” Some of you may recall a note from a few days ago in which I explained my loathing of accounting. Which is math.

I need to say that it has been…some time… since I did basic algebra, and when I saw the graphing equations and the formula for slope ( y=mx +b) I was a bit shaken. The required physics course I took in college was affectionately referred to as “Physics for Poets”. There was no math. Opera singers don’t use much algebra, either.

So we turned on the lights in the dining room. “Get pencils and paper” I told my grandson. He brought two sheets. “That’s not enough.” There was no way I was wasting my precious writing notebooks for this.

And so, we began—both somewhat irritable—to review the past two weeks of eighth grade math. He was gleeful when I made a mistake, and sullen when I was right and teacher-y. And that gave me insight into how to help. So, I told him I couldn’t remember how to do it—which was sometimes true—and he had the fun of explaining to ignorant me just where I had gone wrong. Sometimes I genuinely was wrong, and sometimes I had to be right to explain where he had gone wrong. Old Person Sidebar: Why don’t they teach kids multiplication tables anymore?

But I have to admit, even if he dramatized how much he hated it (“Why do I have to do math? I’ll never use it.”) I was positively joyful that I could access the algebra file drawers in my brain.

Later, I told my husband the kid had better never take Calculus because I wouldn’t be able to help him. We giggled.

After two hours, we had gone as far as we could in one evening, and when my grandson came back downstairs in his yellow pajamas, he had hot chocolate, and I had two whiskeys.

I feel I earned them.

***

And now your gratuitous dog photo.

We didn’t celebrate St. Nick’s Day when I was a child. I hadn’t even heard of it until we moved to Wisconsin. And it didn’t occur to my parents–who were not big on following along with the crowd–to adopt the local custom. I never felt deprived.

But St. Nick is a thing, both among the local families, and according to French custom, so with our French/American grandson living with us this year, the old fellow was expected to make an appearance at our house. I bought candy and clementines and a rather beautiful US Passport Christmas ornament, and felt I had met the mark. But when we heard that little brother in France got earbuds, we realized we had to up our game. So a late-night emergency trip to the local drugstore yielded a pocket retro electronic game which Grandpa had observed being coveted, and a crappy-cheapo plush Santa hat, which, apparently, is a middle school thing. St. Nick has dutifully delivered these treasures into the depths of the très chic name-brand boots we bought for the non-existent snow.

The boy is happy. And so are we. Kids make the season more fun. Although the game makes a familiar and annoying electronic noise that may drive me mad.

Should have bought the earbuds.

You will have to believe me that a magnificent buck was outside my window this morning. I looked away for a moment, and when I looked back he had melted into the camouflage of leaves and bark, still, invisibly, there.

I have come to believe that the invisible things are often the most important. These are the things we feel intensely and sense around us: maybe passion, maybe tension, maybe danger, maybe the proud buck in the trees.

Advent is an invisible thing, too, covered in mystery and in the deepening darkness of the earth. I don’t think it’s contradictory, or even surprising, that in this time when the earth stands sleeping we should await, with hope, the promise of light and new life. Because whether you accept the theology or not, those things are coming, literally and visibly.

But it is the invisible that beckons, that clutches the heart and draws us deeper.

And as winter comes, that silent moving of the universe is the darkest, deepest mystery of all. What is eternal? Can some part of us be eternal, too? What is this thing that I am, that wakes, and dreams, and sees the stars, and speaks to the souls of the trees? Why am I here, this small thing, trembling at my mortality while soaring out to meet the edge of sky?

The human soul has seasons, and the earth, wheeling through darkness and light, prepares us for them.

We wait. And we watch, filled with hope and awe.

We live in the country. So, when the temperatures dipped into the teens this week, of course, that brought an influx of mice.

Mice are a houseowner’s horror. They are destructive, filthy, and carry disease. But—and I know how this sounds—I cannot bring myself to kill them. I see their big black eyes, and their tiny feet, and they are so frightened and vulnerable. They are like very tiny puppies.

By the way, did you know that mice sing to one another?

So I buy humane traps, bait them with the dogs’ freeze-dried liver treats, and early each morning load my catch into the car and drive out to a cornfield a little more than three miles away. It must be three miles, because, apparently, mice can find their way back over any smaller distance.

Yesterday I caught three. My 13 year old grandson willingly accompanies me because we stop for a doughnut afterward, and he then gets a ride to school. It’s a bit of an adventure.

Last night I set three regular traps, and something new: a bucket trap, with a little ramp and a trap door. I filled the bucket with dried leaves for a soft landing, and smeared the top with peanut butter with dog treats stuck into it. Although I can’t be sure whether anyone is in there this morning, there is a hole in the center of the leaves which suggests there might be. I’ll know when we get to the cornfield. When I dump out the bucket I will be sorry to lose the cache I’ve saved of dry leaves for soft mouse landings, but it can’t be helped.

I don’t know whether the farmer has noticed a car stopping by his field in the early mornings, but it’s a nice field, with corn stubble and lots of kernels scattered in a mouse-friendly way. I have some minor concerns about whether the mice are too cold, but I am doing my part. They are on their own now.

Godspeed, mousies. Don’t come back.

Dad’s working late tonight, but I have lovely company. Since Auggie’s illness the Germans have grown more affectionate with one another. I see them through the kitchen window as they’re playing together, and it surprises and delights me. They romp and hide and pounce on one another just as Moses and Auggie used to do. I’m not sure what’s different, but maybe dogs share with human beings the appreciation of things almost lost.

We are in bed with a fire in the fireplace and some Irish whisky to go along with a good book. The dogs are not particularly interested in whisky or books, but they do enjoy comfort.

Sweet dreams.

Life is almost back to normal. Auggie’s fur is growing back, and he’s full of spark. He does have one wilting ear, which we think is the result of wearing a cone for a month and accumulating moisture. Back to the vet we go! I’ve suggested to the clinic receptionist that when I call he should respond “Now, what?”

Ah, Monday. Blessed-nothing-planned-no-appointments-on-the-calendar Monday.

We traveled for the holiday, and while it is always good to see family, it is also good to be at home in your own bed, and then waking to watch the sun rise, with the silhouettes of deer and turkeys in the woods, and the sweet soft breathing of big dogs nearby.

When I had a day job my Sundays were filled with dread. On Monday mornings I would stand at the big windows of my bedroom looking out at the beauties of the woods and sky, feeling bereft at having to leave for the demands of the classroom or office.

Now my schedule is mostly my own. And because I have always hated that Sunday feeling, I try to never schedule anything on a Monday. I write in the mornings, and reserve afternoons for appointments, errands, exercise, and domestic tasks. Lately, however, in what seems to be some kind of mechanical conspiracy, we have been on a breaking-down appliance spree, so my autonomy has been interrupted by lengthy bouts of dishwashing and repairmen who schedule their appearances in five hour appointment windows. Today, I have nothing planned except writing, walking the dogs, and making beef stew. There will also be a long, fragrant bath. A perfect day. I hope.

But we never know, do we? Our expectations of perfection are mostly disappointed, and since disappointment is a form of ingratitude, it would be graceless not to appreciate the imperfect blessings of our real lives, no?

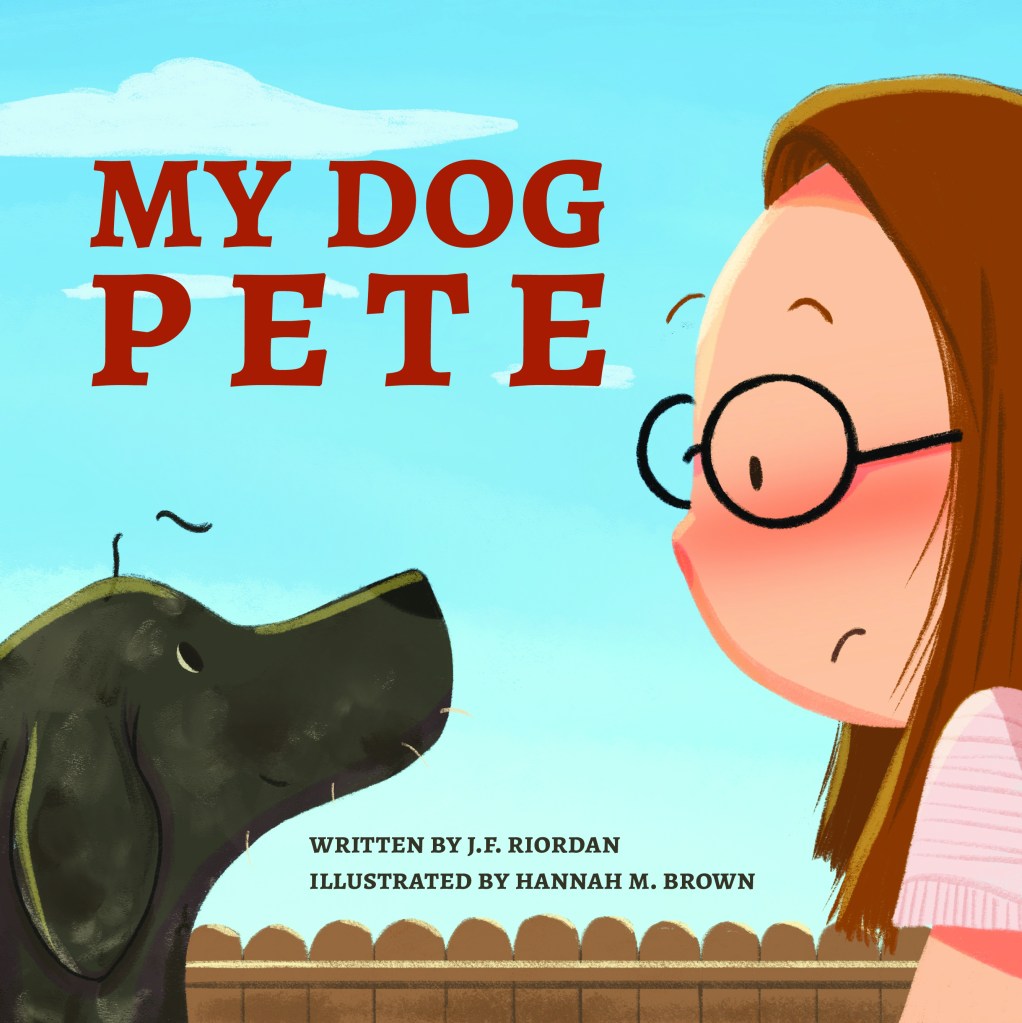

And this brings me to My Dog Pete, the children’s book I finally got around to publishing this year after more than a decade of leaving it to languish in a file in my office.

My husband, who is a man of deep insights, recently pointed out to me that the book contains the philosophy of a happy life. I heard this with some surprise, because I was only telling a story, not trying to convey a moral. In the book, a little girl wants a perfect, golden dog who will be handsome and admired. Instead, she gets a mixed-breed, mischievous shelter dog who was probably abused, leaps as gracefully as a gazelle, and smells a little funny. She doesn’t want him. But–spoiler alert–against all her heartfelt preferences, she falls in love with him.

So often in life, when things don’t live up to our expectations, we are frustrated and disappointed. And yet, most of the time, what we get–even though it isn’t perfect–is still something good, and we are lucky to have it.

We must notice the good things we are so blessed to have. Ingratitude is a sin, and in most theologies perfectionism is, too, because it is a focus on self-will and the ego. And also because for most of the world, sadness and misery is a normal day. So now, when one of us doesn’t get exactly what we hoped for or expected, we say to one another: “I wanted a golden dog.” And we remember to relax into the reality of imperfection that is still filled with many beautiful things; many blessings.

After all, in real life we didn’t expect it, but we got Pete. And we wouldn’t have changed him for any other dog in the world.

Hoping you had a Happy Thanksgiving.

A friend and I went to a local greenhouse to make Christmas decorations with greenery and red trimmings in big outdoor pots. It was a lot of fun, and felt like the beginning of something both old and newly sweet. In the spring and summer, the seven greenhouses overflow with plants and flowers, but now everything smells like balsam and spices, and there are poinsettias, and garland, and wreaths, and hanging balls made with evergreens and sparkly things. It struck me sharply how much we need the presence of green things amid the darkness and cold of winter.

The family who own the nursery are fifth generation in the business, and the current manager told us of her great-grandfather who had been buried alive in World War I, and survived in an air pocket, eating the shoelaces of a dead comrade. He came home to his wife who had been told he was dead. Together, they began nurturing growing things, which seems both beautiful and significant.

In my family we have keepsakes: furniture, Persian rugs, silver, an ancient Bible, paintings and photos. And we have common threads, too: a love of learning, of literature and art, a passion for freedom and an expectation of basic decency. But I think about what it must be like to be upholding the family’s work in such a particular way, with all the significance and restrictions, resentments and pride that must come into the mix. All the generations–male and female–were represented at the nursery; they all seemed skilled and cheerful: laughing while disagreeing about the right way to place the boughs in a planter, teasing one another, singing along with the corny Christmas music, putting floral stakes and tape on pine cones and big shiny ornaments, and helping us create the right shape for our arrangements. They worked well together.

As we were leaving, we stopped to look at this old stone building next to the gravel parking lot. It was a poignant reminder of a family’s history.

And I like that.

Writing bad poetry is a pastime shared with youth and age. I will spare you mine, but intense emotion always draws it out of me, and I hide it as if it were an addiction to drink or pornography. I am so grateful that Auggie is home. And he is back. This is not redundant.

His stitches are out; the cone is off; his obsession with balls is unabated; he is romping nearly at full speed, and he seems to have a new appreciation for home, and bed, and snuggles. He is insatiably hungry; all I do is feed him. I don’t even need to tempt him. He is healing and his body needs to rebuild.

We almost lost him more than once, and we are so grateful to have him back, whole in every meaningful sense of the word, and sound. But he seems to have muted just the smallest bit, noticeable only to those who know him, and suddenly he is no longer young and immortal, but middle-aged and vulnerable like the rest of us.

We took him in for a check-up and sat studying the veterinary wall chart on dog sizes and lifespans. At six, Auggie is now well into middle age, and his life may be more than half over. His family have lived to twelve and fourteen. While that makes me vulnerable to hope, those ages are not common for big dogs, and Auggie is a lean 112 pounds. Mortality lingers in the background for all of us, but dogs have those first sparkling years, and then the slow sadness creeps in too quickly.

I used to scoff at people who said they couldn’t endure the pain of losing another dog. Now, I’m starting to get it.

But meanwhile, here they both are: vibrant, restless, and ready to run. I’d better go.